As someone who’s learned mainly by ear for 20 years, I can vouch that it does get easier the more you do it. But even the best aural learners get stumped now and then (usually on some simple 4-note sequence that just doesn’t click). After you’ve played this music long enough, you’ll start giving yourself the excuse that some tunes are “counter-intuitive” — the notes don’t go where you’d expect them to. And that’s okay. Part of what keeps me playing Irish music is its infinite variety. If I could figure out every tune the first go round, I’d be bored. Just persevere and be patient with yourself.Will Harmon

Fiddle/Whistle/Juggling

Montana, USA

Learning to Learn by Listening

Learning to learn tunes by ear is one of the hardest things to do when you’re just starting to do it. The process is seriously intimidating and almost feels impossible at times — but don’t give up! Every good Irish traditional musician learned to do it at some point or other. We can all relate to your frustration. So take a breath and be patient with yourself.

Tony MacMahon once said that Irish trad music is “more learned than taught.” It sounds like a Berraism, but it isn’t. To learn to play the music well you have to push yourself, the drive has to come from inside, and you have to have the right idea of it to get it right. This will also be a source of some frustration. Mentors, teachers, or instructors can help you a great deal, but that will be mostly by pointing out pitfalls and technique problems. With trad, most players are primarily self-taught, secondarily instructed — though good instructions can save years of bad technique and bad rhythm. We’ve all gone through the stages of self-doubt and (some) success. Like distance running, more than half of the game is mental. The work comes in the form of thousands of hours of listening, and listening more closely, and then playing. Being self-critical, and finding ways of addressing faults. That’s what it takes to be anything from a well-respected regional player to a world-class player. It is up to you how far you want to go.

![]()

Answers to Questions:

- Why learn by ear?

- What skills do I need to acquire to learn by ear?

- Who should I listen to?

- Ok, but really, how do I learn by ear?

- Where Else Can I Look?

![]()

Why Learn by Ear?

There are many reasons why you should learn to learn by listening. If you went around asking people who can do it, you’d get a variety of answers. What follows is a list of some of the most common answers.

- AURAL learning is how traditional music is taught everywhere! If you ever go to a workshop, or festival with master classes, or anything like them, then you’ll discover that what they all use is the basic call-and-response aural learning technique. The sooner you learn how to learn like this, the sooner you can pick up great tunes from world-class players.

- Tunes are not always available in written form. While there are dots for many tunes, there are far more that are not written down. Often you’ll hear a great tune just whiz by without knowing its name or anything else about it. If you have someone who knows the tune, then the answer will be the same as the one above. If you don’t, then you can record the tune and learn it from the recording, but only if you can learn by ear.

- Trad music is very difficult, if not impossible to notate as played. For example, changes in bow pressure, subtleties of phrasing, ornaments, etc. There is standard notation for bow direction, but it’s rarely used for folk music. As with any style of contemporary folk music, and with early classical music, the written sources are nothing more than a rough indication of what actually gets played.

- Ear LEARNING makes you a better player. Every player approaches a tune differently, and each repetition of the tune should aim to be unique. Learning by ear helps you become more attuned to these differences, and makes your own playing more varied and interesting. When you learn a tune by ear, the tune seems to enter a different part of your brain―the part that’s directly connected to sound and music. Though reading music is a very useful skill, when you stare at a piece of paper while you play you’re taxing your brain, making it do visual processing, instead of aural processing. For some people the visual processing makes it almost impossible for them to do some or all of the following: listen to what you are playing, to listen to what others are playing, pay attention to how you are handling your instrument, be cognizant of your body, draw the rhythm into your body. When you play your eyes should be used to make contact other musicians or the audience. Staring at the dots on the page makes you oblivious to what is going on around you — just like walking and texting, or worse driving and texting.

- The tunes are REALLY living tunes! A tune really does have a life of its own―it’s not static bits of ink on paper. People often notice regional variations in a particular tune, but that’s only a small part of the story. As mentioned above and below, tunes are really always already works in progress. Maybe it’s something like the old telephone game coupled with natural selection―each playing of a living tune is different, and the better variants tend to persist. When you learn a tune by ear, you become an active part of this creative process. When you learn “by the dots” you just don’t.

- Music IS live music. Back in the misty past, the only music there was was music that actual people, living breathing human beings played. The word “music” at that time just meant “live music.” If you wanted to learn a tune, then you had to pick it up from a living, breathing player. Then some mere seconds of geological time passed, and folks used to go out and “buy music,” which meant that they purchased dots on paper and brought it home to play on the sousaphone they kept in the corner of the courting parlor. One second later the CD was invented, and you’d hear more talk of “buying music” when just purchasing a CD. As a result people got confused about what music really is. Very confused. Don’t you be fooled by such figures of speech. It is still the case that the only music there is is music played by a living, breathing person. Everything else is just a replica. Statues look like people, but just try talking to them! A reflection of a tree is not the thing itself. A dot on a staff is not a tone even if it has a flag. (Though it seems by the way some folks treat them, the dots must be sweet like candy!) Keep in mind that an image of a vat is just an ersatz vat, not a real vat, and you can’t climb in or out of it no matter how you try. Anyway, to belabor the point a bit more, a picture of a landscape is not an actual landscape — though someone might say “I bought a house in Ireland” and mean that they bought a picture of a house in Ireland. I bet you’d be able to tell the difference. Yet, a recording of a guitar chord is sometimes really thought to be a musical chord. The recording of a song is really thought to be a song. The recording of a tune is really thought to be a tune. Still, believing doesn’t make it so. Being reflective about reflections helps us to not be fooled by imitations. If it’s not live, then it’s just dumb old Memorex.

- Aural learning is NATURAL. Just as children speak before they read words, and sing before they can sight sing. Playing by ear is a small step from singing by ear. It just takes a little more ear-hand coordination.

- Aural coordination is FUN. Developing coordination between your ear and your hand(s) is actually easier than between your eye and your hand(s), it just takes a bit of practice. And it’s fun!

![]()

What Skills Will I Need?

These are skills you will need to work on, and you can do that anywhere:

- Develop your Pitch Sense: Note whether the tune goes up or down, and start to recognize intervals (i.e., the jump between notes).

- Recognize Time signatures: What is the pulse of the tune? How are the beats grouped?

- Focus on Phrases: Listen to tunes by chunking (breaking them into smaller phrases)

- Determine the Key/Mode:

- On what note does the tune resolve?

- What is its mode? (hear the intervals: major third or minor third? flatted sixth or not?)

![]()

Who Should I Listen to?

I have been asked often enough questions like “Who should I listen to play traditional music in the right way?” The short answer is “every great player you can!” The fact is that there are a range of right ways that can express the sense of this music, just as there are many good ways to read a poem, or produce a play. However, this doesn’t mean that anything goes. It means that there’s more than one way to play tunes as part of this living tradition. There are also many more ways NOT to play in the tradition. It’s especially unfortunate when a player wants to play in the tradition, but is mistaken. Listening to great protagonists of the tradition is essential. When I first came to this music I literally stopped listening to anything else for about three years. I realize, however, that the trad players I’m especially fond of are not everyone’s favorites. There’s room for differences in taste. So this list is not definitive or exhaustive. It’s just a place to start.

1. I’ll start with some free places to listen to great musicians well within the tradition:

- Ceol Alainn’s out-of-print archive

- Bill Black’s Tune Vault

- Ross Anderson’s Music Page

- Juneberry 78s Listening Room: Irish Dance Music from the 1920s-70s

- ITMA Recordings

- British Library of Sound

- Library of Congress, USA

- Alan Lomax Recordings

2. Here’s a short list of contemporary world-class players of interest:

Donal Lunny – a force in Irish music, bouzouki player.

Andy Irvine – respected veteran of Planxty, Patrick Street and many others

Paddy Keenan – reknowned piper from the Bothy Band

Aly Bain — a great Shetland fiddler,

Natalie MacMaster – a Cape Breton fiddler who has become a megastar in trad music

Sharon Shannon – an extremely popular accordion player from co. Clare.

Kevin Burke – one of Ireland’s greatest fiddlers, and member of many legendary groups.

Angelina Carberry – a great Irish tenor banjo player!

Martin Hayes – world-renown Clare fiddle player.

Josephine Marsh – accordion player from Ennis, Co. Clare.

3. Here’s a short list of contemporary trad bands:

-

- Seán Ó Riada’s Ceoltóirí Chualann — by most accounts, the original

- Planxty — a powerhouse and ground-breaking band,

- Bothy Band — an early leader in the Irish music scene, 1974-79

- The Chieftains –

- Kíla – formed in 1987

- De Dannan —

- Dervish —

- Patrick Street

- Solas —

- Altan – a tremendously popular traditional group from Co. Donegal in Ireland.

- Lúnasa — a popular Irish band formed in 1997.

4. Traditional Musicians From Clare:

-

- Martin “Junior” Crehan, fiddle (co. Clare: 1908-1998)

- Bobby Casey, fiddle (co. Clare: 1926-2000)

- John Kelly, fiddle (c. Clare: 1912-1998)

- James Kelly, fiddle (co. Clare: b 1957)

- Willie Clancy, uilleann pipes (co. Clare: 1918-1973)

- Tony MacMahon, accordion (co. Clare: b 1939)

- Kilfenora Ceili Band (co. Clare:

- Kevin Crawford, flute (co. Clare:

- Noel Hill, concertina (co. Clare:

5. For reels it may help to listen to these examples:

- Eddie Corcoran & Séamus Tansey, “Bonnie Kate/Jenny’s Chickens,” track 12 on The Breeze from Erin – Irish Folk Music on Wind Instruments (1969): tambourine/bodhrán and whistle

- Andy Irvine And Paul Brady, with Donal Lunny and Kevin Burke, “Fred Finn’s Reel / Sailing Into Walpole’s Marsh,” track 3 on Andy Irvine & Paul Brady (1976): guitar, bouzouki, and fiddle

- Josephine Keegan, “The Kylebrack Rambler/Gerry Cronin’s,” track 1 on Reels, Jigs, Hornpipes, Airs (1980)

- James Kelly, “Sporting Paddy/Doctor Gilbert’s,” track 3 on Capel Street (1998)

- Le Ceoltóiri Cultúrlainne, “The Wind that Shakes the Barley,” track 92 on Foinn Seisiún 2: Traditional Irish Session Tunes (2006)

- Arty McGlynn & Matt Malloy, “Doctor Gilbert’s Reel / Queen of the May,” track 10 on Music At Matt Molloy’s (2007)

6. This is a short list of traditional players from previous generations that you should listen to.

- Finbar Dwyer, accordion (co. Cork)

- Julia Clifford, fiddle (Sliabh Luachra: 1914-1997)

![]()

Someone once said “If you keep trying to learn from sheet music it will always sound wooden and lifeless.” Now that’s both true and meaner than it needs to be. Sheet music seems like a necessity for those starting out. Of course, the skill of reading music right off the page is impressive – I can’t do it well at all. It is ONE skill, and a musician needs to also develop the skill of learning by ear because sheet music is an undoubted distraction when playing well with others in a trad session. That’s because there is a whole lot of interesting individual expression that is just not “on the page.” So choose just one recording of it that you really like, and study it. Use slow-down software to get it slowed down to where you can pick out the individual notes. Learn it note for note, paying attention to where she/he puts the ornamentation, and other diddley bits.

![]()

OK, But How Do I Do It?

“Learning by ear depends a lot on knowing where the notes you’re hearing are found on your instrument. Someone totally new to an instrument probably needs a basic introduction to scales and half- and whole-step intervals before they can begin to learn tunes by ear. Even intermediate players will struggle mightily if they try to learn a tune by ear in a key they’ve never played in before.”

Will Harmon

First, relax. There is no such thing as learning a tune perfectly. Small variations are fine, some are better than fine, and others are better than that. The sour ones, not so much. But there are lots of ways to play a tune. Traditional music is about passing on musical ideas. People are different, tunes will be too. This is what makes it a living tradition as opposed to the other kind. The ideas that follow have been useful to many of us and many of our students. Still, since people learn differently, use what works for you.

- Carry and use a simple recording device. When you hear a tune you like, record it to learn. (You may need to ask permission.)

- Use Slow-Down Software. There is software available now that allows you to play the tune back at a slower tempo without altering pitch. This can be very useful for working out the tricky bits.

- Listen to the tune many times. As Molly McLaughlin says, listen until you can hum it. When you can feel it’s pulse in your body, you are making a good start. If you have a recording, play the tune as background music while washing the dishes or building a porch.

- Then try to figure out what key it’s in

- Then try to work out the notes on your instrument

- Chunk It! Break the tune into smaller chunks, learn each chunk, and then gradually put them all together. A “chunk” can be as small or as big as you like. Its boundaries can be based on musical phrases of any length. You might start at the end, and work your way forward. Work most on the parts that are the most difficult for you.

- Tune Structure. Many tunes have an AABB structure, with each part being a standard length. Some times there are other common patterns: the B part ending the same way as the A part, specific musical motifs (or shapes) showing up in each part. Listen carefully and notice when this happens. When you work on those bits you are working on multiple parts of the tune at once!

- Notice the pulse of the tune. Find the emphasis in the tune that makes it stand out. Think about the pulsed notes as forming the bones of the tune.

- Simplify. Simplify. Simplify. Some tunes are complicated, but the bones are simple. Forget the fancy phrases, take out the fills. Learn the bare tune. THEN add the passing notes, triplets, rolls, grace notes, twiddle bits, filigree, and gingerbread, but only after you have the core of it.

- Pay attention to the shape of the tune. By “shape” I mean the movement of pitches in the tune. Think of the way “tripping up the stairs” starts with an upward shape, and “my darling asleep” starts with a downward shape. Knowing the shape of the tune can be very useful when learning it by ear.

- Pay attention to the patterns of the tradition. Tunes from particular traditions have common traits. Listen for similarities: tune structure, rhythmic patterns, keys/modes, common phrases, etc. Often you’ll find a set of phrases that are repeated across many different tunes, and building up a phrase vocabulary is especially helpful when learning by ear. Polkas and Hornpipes often have expected endings.

- Pay attention to patterns on your instrument. Phrases of a tradition will sometimes be derived from the instruments used. Focus on what you’re actually doing with your hands and fingers when you play a phrase (i.e., the physical pattern) and notice similarities across phrases, as well as across tunes.

- Pay attention to the “hooks” in a tune. Some tunes have very memorable phrases, called “hooks,” that make the tune stand out. Think of them when trying to remember how to play a tune, or how it starts. Memory in general does not work in a straight line, remembering tunes is the same.

- Pay attention to exceptions. There are exceptions to standard patterns all around.

- In some tunes one part is double the usual length (e.g., “Trip To Durrow”)

- In others the parts are half as long (e.g., “The Morning Dew,” the A part of “Monaghan Twig”)

- Sometimes a tune has extra notes (or even extra beats!) at particular points.

- Association. One way to remember a tune is to develop an association that will help you recall it. Who taught it to you? Where and when? Do you have a particularly fond memory of playing it with someone, some place, on some occasion? Think about the setting you’re in when you play it. Go to your favorite places and play your favorite tunes. Make up words that get the phrase in your mind. These and other things can help you recall phrases of a tune.

Some Relevant Links:

![]()

CDs For Slowplayers

Sets in the City – This CD by Tipsy House features music for three popular set dances and a few waltzes as well. It is available through Michael Riemer, Michael Duffy, Martin Sirk or Jonathan Coxhead. It may also be ordered on line from Tipsy House. It’s a great CD and will make a nice addition to your collection even if you are not a set dancer. Click below for sample tracks:

Sets in the City – This CD by Tipsy House features music for three popular set dances and a few waltzes as well. It is available through Michael Riemer, Michael Duffy, Martin Sirk or Jonathan Coxhead. It may also be ordered on line from Tipsy House. It’s a great CD and will make a nice addition to your collection even if you are not a set dancer. Click below for sample tracks:

The Ookpik / The Parting – MP3

Cameronian / Annie Walsh’s / Lads of Laois – MP3

The Godfather / John Kelly’s / John Brady’s – MP3

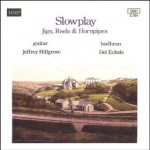

Slowplay – An appropriately named CD by Jeffrey Hillgrove featuring himself on guitar and Del Eckels on the bodhran. Nice simple arrangements at a tempo that would delight slowplayers. This CD is a great tool for those wanting to practice tunes with a CD. It is available on Itunes, or may be ordered by clicking Slowplay. Jeffrey Hillgrove is a regular session player in the Denver area, I believe, plays gigs at local Celtic events, and sits in with a few of the local bands in pubs.

Slowplay – An appropriately named CD by Jeffrey Hillgrove featuring himself on guitar and Del Eckels on the bodhran. Nice simple arrangements at a tempo that would delight slowplayers. This CD is a great tool for those wanting to practice tunes with a CD. It is available on Itunes, or may be ordered by clicking Slowplay. Jeffrey Hillgrove is a regular session player in the Denver area, I believe, plays gigs at local Celtic events, and sits in with a few of the local bands in pubs.

![]()

For a longer list of players go to Traditional Irish Music.

Other Music Sources:

4 Comments

Hello, I’m not certain that Paddy Keenan has played in Moving Hearts. Actually, according to Wikipedia he has rejected this opportunity in 1980.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paddy_Keenan

Thanks edelahaye! I’m not sure where that note came from. I appreciate your good catch on that.

Thanks Nate! I’ve changed the link.

Greetings.

I think by “ITMA Recordings” you might mean: http://www.itma.ie/digitallibrary? It seems to be some link rot.