a teacher with a switch

the way it used to be in school

The term “ash plant” or “ashplant” was once a very common term, and still is in some places. It is a euphemism used by the young and the old. For the young it is a teacher’s stick which would be used to point out important locations on a map, to remind students of something written on the blackboard, or to whack you so hard it would leave a long red welt. So, a phrase like “quit your fidgeting or you’ll get the ashplant!” was once a well-understood admonition. A similar implement, but usually more improvised, has also been used to likewise motivate cows, horses, and sheep. Its use was, I’m sure, as much an endearment to the one group as to the others. By my day the nuns were more civilized, and used a nice heavy ruler, usually focusing on the palm of the hand or the knuckles, but that was in the States, Michigan to be more precise.

Now, for those long out of school the term “ashplant” will refer to something just a bit more hefty than a switch, a walking stick. Ash was the preferred wood because just a few inches below the surface the main root often takes a near right-angle bend for several inches, which then becomes a natural handle when the stick is inverted. So, making one began with simply digging around an Ashplant sapling and cutting it off below the surface of the soil. The rest was just a matter of aesthetics. Seamus Heaney wrote a poem entitled “The Ash Plant” for his father, Patrick Heaney (d. 1982), which has as its penultimate stanza

ashplant walking stick

“As his head goes light with light, his wasting hand

Gropes desperately and finds the phantom limb

Of an ash plant in his grasp, which steadies him.

Now he has found his touch he can stand his ground”

In Ulysses, James Joyce writes of the Aquaphobic and Cynophobic Stephen Dedalus, “. . . taking his ashplant from its leaning place, [he] followed them out and, as they went down the ladder, pulled to the slow iron door and locked it.” And then toward the end of that tome, just after the play, we find this: “Preparatory to anything else Mr. Bloom brushed off the greater bulk of the shavings and handed Stephen the hat and ashplant and bucked him up generally in orthodox Samaritan fashion which he very badly needed.” More recently, in an epic epilogue to Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, we find this: “Grimly, I leaned on my ashplant and said it wasn’t easy; LeVol replied that nothing worthwhile ever was.” (The Heat of the Sun, by David Rain, 2012).

Of course, the names of tunes are not the tunes, and with few exceptions have almost nothing at all to do with the melody. The names are simply tags, at best mere mnemonics. Yet, as mnemonics they only unlock the appropriate part of a memory palace when there’s a practiced path between tune and title. Alternatively, well-worn associates may help. So, one name might have a very functional association for one group of people, but little to none for another. When the key no longer works, the simplest thing is to find something that does. That is just one reason why new names become attached to old tunes, and it is a perfectly legitimate reason. So, don’t be shy if you need to call it something else.

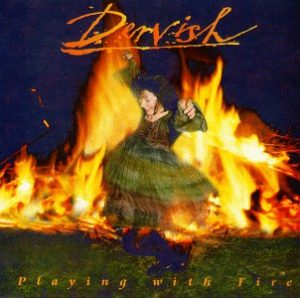

Dervish, Playing with Fire (1996)

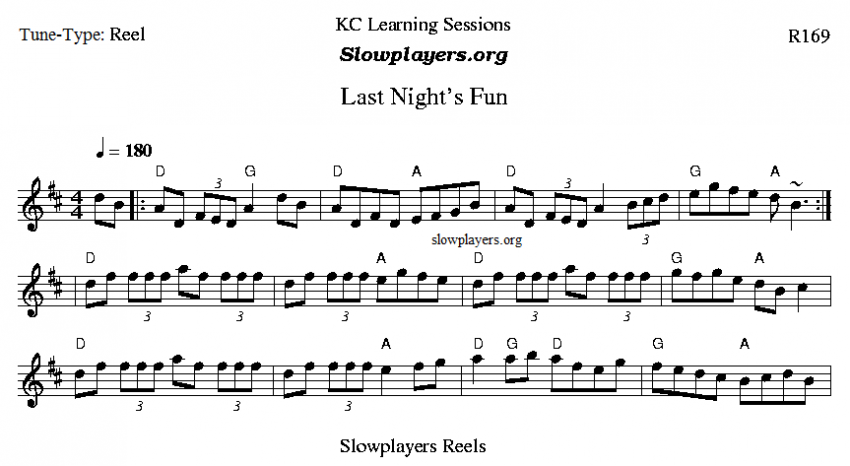

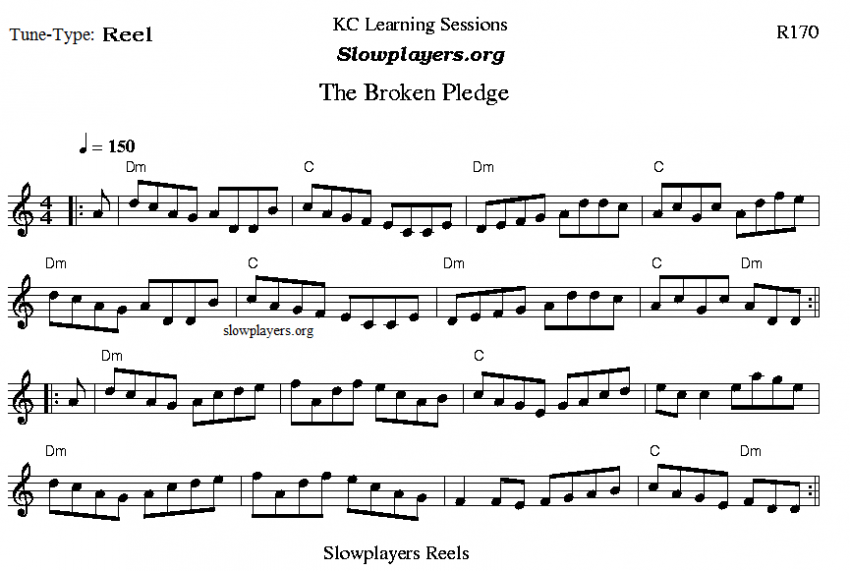

Anyway, this reel “The Ashplant” is called “An Maide Fuinnseoige” in Irish and is usually played in Edor, unless you come across someone who learned it either from the old Dervish cassette Playing with Fire (1996) or from Altan’s CD Blue Idol (2002), where it’s played in F#dor.

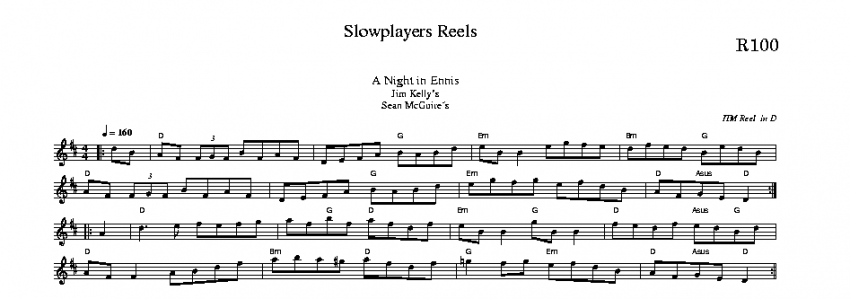

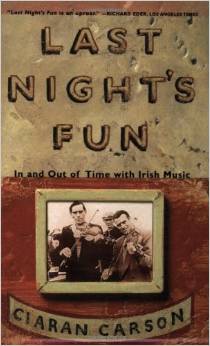

Importantly, there is another tune, a very different reel most often played in D, that is sometimes done under the title “The Ashplant” or “The Ash Plant.” At least that is what it is titled on the eponymous Lúnasa CD (1998/2001), though there played in A, and also in Nigel Gatherer’s Tune of the Week, vol. 2 (2012). Though I first learned that one as “Sean McGuire’s,” from John Doonan’s Flute For The Feis (1972), it is much better known as either “A Night In Ennis” or “Jim Kelly’s.”

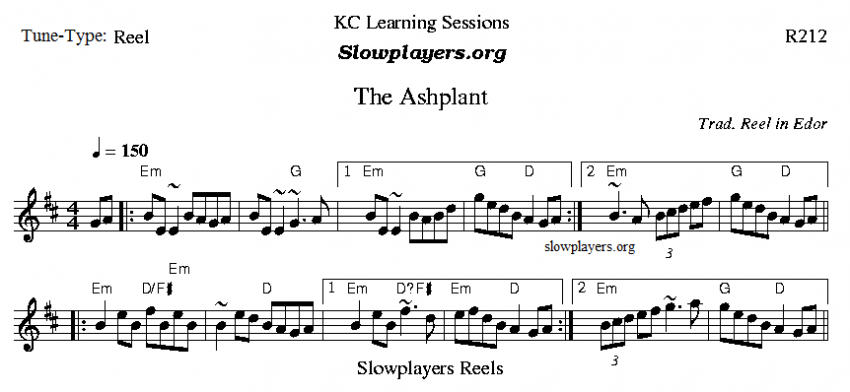

For the ABC click Ashplant

The Ash Plant, slow tempo

The Ash Plant, med tempo

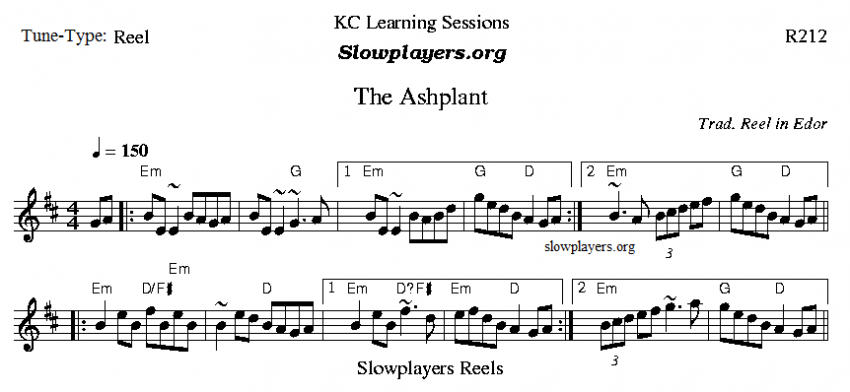

The Ash Plant, the dots

Ashplant, Reel in Edor

Alabama Rick’s (A)

Mike Dugger and Turlach Boylan at Prospero’s Books Sesh in KCMO

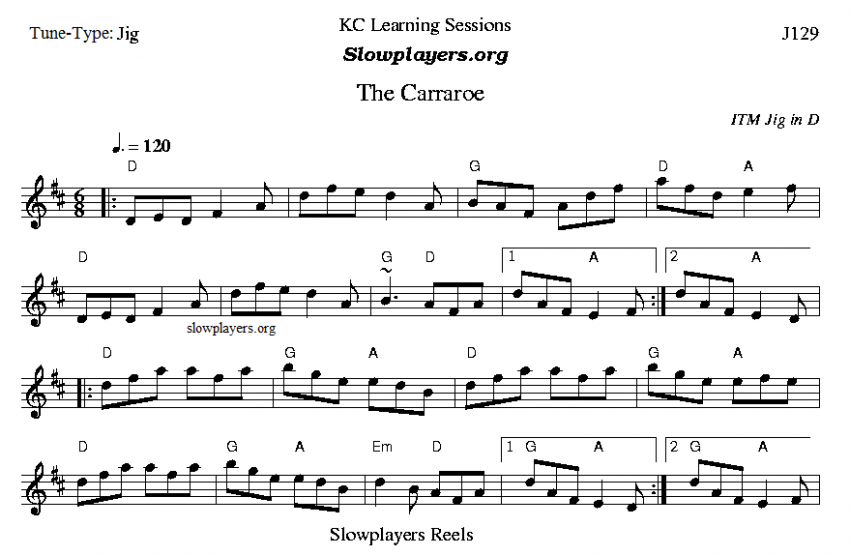

This Jig was penned by my friend Mike Dugger, and has been recorded by a number of different folks. About this tune Mike writes “I wrote the tune in 1997 in my garage when I lived on 10580 Gillette Street, in Overland Park, Kansas. I don’t know where it came from but I had just met Rick Cunningham from Hoover, Alabama at the Swannanoa Gathering and we became, and still are, fast friends. I played it the following year at the Gathering on stage with Roger Landes and Zan McLeod as an opener for the teacher concert and it was a huge hit. It’s currently played a lot in Texas and I have heard from a player in Japan some years ago, that its played over there as well. It’s been recorded by myself, Ken and Peggy Fleming, with Kevin Alewine in Dallas, Texas and a band called Roarin’ Mary out of Virginia.” Thanks for the tune, Mike!!

Alabama Rick’s, Medium

Alabama Rick’s Jig, Fast